I’ve been researching jewelry off and on for the past 6 years, for part of my work that I do with FUTURA Jewelry. Now that I have a Substack, I’m so excited to do a deeper dive and share some of my findings with you all!

Everyone seems to be familiar with Elsa Peretti and Palmoa Picasso, so I felt particularly called to write about some of the lesser-known, but no less incredible, women designers of the 20th century.

Here are 3 fascinating Mid-century designers whose work should be known by all.

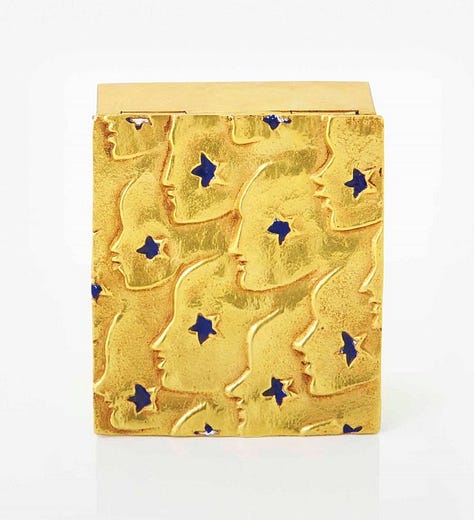

LINE VAUTRIN

Line Vautrin was an artist and jewelry & objects designer, born in Paris on April 28th (my birthday twin!), in 1913. She essentially grew up in the bronze foundry where her family worked, allowing her to pursue her love for metalworking from a very young age. She mastered the craft as a teen and released her first line of jewelry at the age of 21, pursuing an uncommon career for a woman of the time.

Vautrin was a truly independent soul, and in 1937, she exhibited her work at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques, which included not only her jewelry but her imaginative boxes, powder compacts, and ashtrays in gilt bronze, to high acclaim. From here, she was able to acquire a starting customer base.

She worked for a short time with Elsa Schiaparelli, but quickly discovered she preferred working for herself. A few years later, Vautrin opened a boutique in Paris, located on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where she sold her accessories and jewelry, including buttons, bag clasps, and belt buckles. These whimsical pieces gave people a much-needed escape from the stress of wartime hardships, skyrocketing her work in popularity.

In 1948, Vogue proclaimed her the “poetess of metal” for her highly creative pieces and unconventional perspectives. She drew inspiration from nature, ancient myths, literature, and alchemical principles, which clearly shine through in her jewelry, shown below.

In the 1960’s Vautrin discovered a material that sparked a whole new design process and aesthetic, called Cellulose acetate — fine layers of resin. She then added her personal touch by tooling, scraping, inlaying glass, and utilizing fire to create these stunning time-eroded and imperfect textures. She patented it and named it “Talosel”.

She applied this technique and material to every aspect of her work, creating fantastical mosaic-like lamps, jewelry, and mirrors (shown below), which she is now most famed for.

Vautrin closed her shop in 1969 and opened a craft school with her daughter Marie-Laure Bonnaud-Vautrin, where she taught her innovative techniques to aspiring artists. In 1980, she retired, but continued her life of creativity until she passed away in 1997.

Sources: Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Chastel-Maréchal, 1st Dibs

WINIFRED MASON

Winifred Mason was an innovative jewelry designer during the Mid-Century, helping to break barriers for Black jewelers and jewelry designers in the industry. Born in Brooklyn, NY, in 1918, she initially studied English Literature, going on to receive her MA in Art Education at NYU, graduating in 1936.

Before finishing her Master’s, she began making jewelry in her parents’ Brooklyn home, creating designs to her taste that she couldn’t find in any department stores. Her jewelry quickly gained popularity among the women in her communities, only increasing as she finished her degree.

After graduation, she began teaching arts & crafts classes at a non-profit youth organization in Harlem called the Works Progress Administration (WPA) . There she met and mentored Art Smith, who would go on to become one of the era’s most famed jewelry designers.

Her work was heavily influenced by Africa, and its Diasporas, creating a unique style that stood out within the prevailing Mid-century design landscape, which was often dominated by European sensibilities. She was inspired specifically by patterns of West Indian cultural traditions. She crafted her one-of-a-kind works of art in copper, later expanding to bronze, silver, and pewter, often using two or all metals in one design. Mason prided herself on handcrafting each piece, so no two were exactly alike.

Through the medium of jewelry, I shall aim to express the desires and aspirations of the West Indian people, which are parallel to the desires and aspirations of the American Negro or any other group which has felt the yolk of oppression and injustice.

Source: The National Museum of African American History & Culture

In 1940, she opened her first workshop in Harlem, becoming a popular place for Black craftspeople to train and work, including Art Smith. In 1943, she moved her studio to Greenwich Village. Her work was in high demand, and shops like Lord & Taylor and Bloomingdale’s carried her pieces, and many consider her to be the first commercial black jeweler in the USA. Her list of clientele was vast and commissions abundant, among them being Billie Holiday.

By the late 1940s, she was a powerhouse name, with solo exhibitions in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Port-au-Prince in Haiti. In 1945, she received a grant from the Rosenwald Fund to research traditional folk art and metalworking in Haiti. There she met her husband, a fellow artist and jewelry designer, Jean Chenet.

Source: Sotheby’s

She split her time between Haiti and NYC, selling her jewelry at shops in each location. In 1948, Mason, now Mason Chenet, opened a store in NYC, called the Haitian Bazaar, specializing in imported Haitian art, jewelry, and fashion.

Together with her husband, they created a jewelry business in Haiti, designing Vodou-inspired pieces that catered specifically to tourists, called “Chenet D'Haiti”. They wanted to dispel the negative stigmatism held by the West regarding the Vodou religion and created pieces that highlighted its beauty, symbols, and iconography. Below is an example of a pair of earrings they designed together.

Source: The National Museum of African American History & Culture

Tragedy struck in 1963 when her husband, Jean, was murdered by the Tonton Macoute, a paramilitary group in Haiti. This prompted her to move back to the US permanently. Later on, Mason Chenet focused on championing other Black women artists and was honored by Girls Friends, an organization that helped foster community and uplift Black women in the US.

Sources: The National Museum of African American History & Culture, Sotheby’s, IGI

ANNA-GRETA EKER

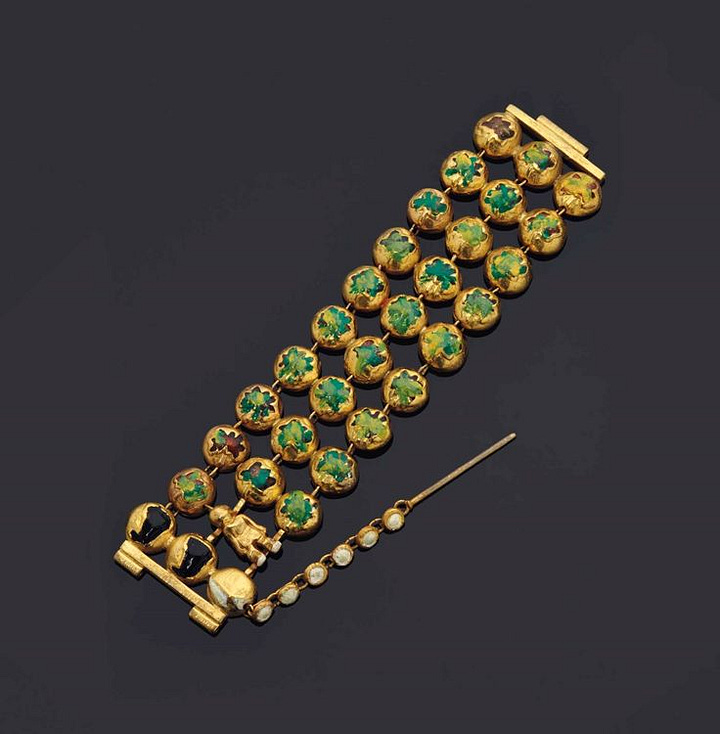

Anna-Greta Eker was born in Åland, Finland in 1928. She attended the Ateneum School of Crafts in Helsinki and graduated in 1951. After school, she worked as a designer for a goldsmithing firm called Hopea Keskus in Hämeenlinna.

In 1956, she moved to Germany to intern for another goldsmith, meanwhile honing her skills by attending additional jewelry classes at the Schwäbisch Gmünd University of Art and Design. There, she met her future husband, Erling Christoffersen, who was from Oslo, Norway.

She moved back to Finland and worked for a firm called Auran Kultaseppä, where she designed and made this tulip-inspired candlestick holder, gaining her recognition and success as a designer.

She ended up marrying her old classmate Christoffersen in 1959, and together they moved to Norway and started working with an innovative applied arts organization called PLUS.

Eker’s jewelry for PLUS became some of the best-selling items in the company's catalog. In 1977, the famed Japanese jewelry house, Mikimoto, visited PLUS to see Eker, and she was invited to design some jewelry for them. Together, they created a small collection of necklaces, earrings, and rings using Mikimoto’s famous pearls, released in 1984. Unfortunately, I could only find one image from the collaboration, shown below.

In 1979, Eker was granted an Artist stipend from the State, allowing her to focus less on making commercial work, and she eventually opened up a workshop and a storefront. In the 1980s, she began experimenting with different materials like leather, wood, fossil, brass, and copper.

She drew inspiration from nature through a Scandinavian perspective, crafting playful and quirky jewelry, called “portable sculpture” by the design house PLUS. Her work embodies the aesthetics of mid-century design and was often referred to as a pivotal figure in 20th‑century Scandinavian jewelry.

I can’t seem to find much about her end of life, only that she passed away sometime in 2002.

Sources: Norwegian Encyclopedia, H is for Her

That wraps up three women jewelry designers of the Mid-century! Were you already familiar with any of these incredible designers? Drop them in the comments below.

I have a couple more women that I would like to write about, so let me know if you’re interested in reading about them as well!

Great post.

More posts about past jewelry makers would be good.

Line Vautrin’s work is brilliant.

She will, hopefully, get a shout-out in my work-in-progress novel, once I get to the appropriate point.